This is the time of year where we see an over-abundance of colic cases in the north. This past weekend I saw 3 colic emergencies – 2 of which needed surgery to survive. Despite “colic” being a common malady in horses, there are many misunderstandings regarding this disorder/disease and how it can or should be treated. When presented with a case of colic the most important question the veterinarian has to answer is whether the cause of colic can be treated medically or if surgery is necessary. “Colic” is too general of a term to go over in one post, so in this post I will just try to explain how your vet decides if the horse needs surgery or not.

Quick review – what is colic?

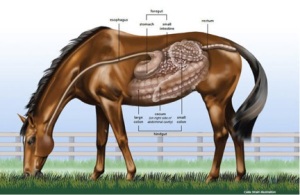

“Colic” is a general term for abdominal pain, meaning any organ or place in the abdomen may be causing the pain (stomach, GI tract, liver, etc.). When we see a horse showing the signs of colic the only thing we know for sure is they have some pain in the abdomen. The challenge to the veterinarian is to see where the pain is coming from and what is causing it. For this post I am only going to discuss gastrointestinal causes of colic.

Certain disorders that cause colic symptoms are more common than others, and there are clues your vet uses to deduce which is the most likely culprit in each horse they examine. Some important factors your vet considers are the horse’s history, age, diet, environment, and breed. For instance, if I am out to see a colic case where a horse lives on sandy soil with little pasture I will be very weary of a sand impaction.

What is the difference between medical and surgical colic?

A “medical colic” refers to a case of colic that can be treated with medicine and supportive care, whereas a “surgical colic” requires opening the abdomen surgically and physically correcting the problem. Let’s think of the horses’ GI tract as a hose, with water coming in at the mouth and exiting out through the rectum. If suddenly the water stops coming out, naturally you are going investigate to determine why the flow has stopped. If the hose got plugged up with debris you may be able to clear the debris using various chemicals or hot water to break up the plug – this is similar to an impaction colic that can be treated medically. However, if all of your remedies did not work and the hose was about to burst, you may decide to open that section of the hose and physically remove the debris before repairing that section of hose. The second scenario is like an impaction colic that needs to be treated surgically.

Source: medicaldictionary.com

Still using the hose analogy, let’s say that the hose got twisted up and kinked, and thus stopped running. No amount of chemicals or hot water that you try to put through the hose will fix that kink and twist. The only way to correct the problem is to manually untwist the hose and put it back in place. This scenario is like a displacement or twist of the GI tract, which can only be corrected with surgery.

How do you know whether a colic case needs surgery?

The general physical exam will help your vet figure out the severity of the colic case. Rapid heart rate and sweating can indicate severe pain. Dry mucus membranes tells the vet the horse is dehydrated. The absence of GI sounds can indicate that the bowel is not functioning. Aside from the physical exam, there are other tests your vet uses to determine if your horse needs surgery or not.

1. Response to pain meds – The most important way your veterinarian determines whether your horse needs surgery is by his response to medical therapy and pain medication. If the pain is not controllable despite strong painkillers and anti-inflammatory medication, then something is not right inside and there is a high probability that it can only be fixed with surgery.

Source: peasebrookequineclinic.com

2. Rectal examination – When your vet puts on a long plastic glove and squirts a bunch of lube on it, it can only mean one thing :)! However gross it may be to some individuals, it is an important tool that lets us palpate a portion of the GI tract and abdomen which cannot be seen with an x-ray or ultrasound. We may be able to feel a hard, impacted colon, indicating the possibility for medical treatment. Other times we may feel like all of the GI contents are pushed to one side, indicating a displacement which most likely needs surgery.

3. Reflux (vomiting) – A horse physically can not vomit like humans and dogs and cats because of their anatomy. The sphincter muscle that closes when something enters the stomach is very strong, plus the esophagus enters the stomach at an angle which makes it hard to push the contents back up into the esophagus. So when the stomach contents are not emptying into the rest of the GI tract they start to accumulate in the stomach and cause it to stretch (which in turn causes pain). If this happened to us humans we would just throw up to relieve the pressure, but the horse can not do this. This is why the vet will stick a tube down the horse’s nose and into his stomach, which essentially allows for the stomach to release its contents orally. The reason that this treatment/diagnostic test is so important is it give us a clue as to how long the problem has been going on and how severe the blockage has become.

Source: chinovalleyequine.com

There are many other tests that a veterinarian can use to determine the necessity of surgery, but the top three listed above are the simplest and most direct. However, until we actually open up the horse we can’t say if the colic would have gotten better with surgery or not. Because of this most veterinarians will give you probabilities when it comes to determining how to treat a colic. For instance, one case this weekend could not be controlled with pain medication and had a rectal exam that indicated there was a major displacement of the GI tract. I could not say that I was 100% percent sure that the horse needed surgery to survive (nothing in medicine/surgery is 100%), but I did say I was 99% sure that was the case. In another case the horse responded OK to the pain meds, had a normal rectal exam and no reflux. Because he still was a bit painful despite medication, we kept him in the hospital for IV fluids and observation. At that point all I could tell the owners was that he was most likely going to be fine but I wanted to make sure he was pain-free before sending him home. After 3-4 hours he appeared fine, wanted to eat, and passed feces, so off he went.

I hope this post makes it a bit easier for the reader to understand how vets know when to send a horse to surgery and why some colic cases need surgery but others don’t.

Please feel free to email me with questions or future topic requests!