I hope you enjoyed reading about Misunderstood, Misused, & Misdiagnosed Disease #1: EPM. In that post I explained how some horse enthusiasts (trainers, owners, etc) have used this disease to explain any number of abnormalities that their horse is exhibiting. EPM is quite a convenient disease to blame for oddities because it affects horses in so many different ways.

Another disease that I have found that is easy to over-use as a diagnosis is Lyme Disease. In this post I would like to briefly explain what Lyme disease is, why it is easy to misuse as a diagnosis, and how a veterinarian evaluates a horse to determine if the Lyme Disease is responsible for the clinical abnormalities that the horse exhibits. I will not get into the complex pathology and treatment options of Lyme Disease in this post.

Lyme Disease is one of several nasty diseases that can affect multiple species, including humans, dogs, and horses. It is caused by spirochete bacteria named Borrelia burgdorferi (Bb). These spiral-shaped bacteria are transmitted to humans and animals by species of Ixodes ticks. The deer tick or blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis) transmits Lyme Disease to humans and animals on the east coast and north central United States, while the western blacklegged tick (Ixodes pacificus) is responsible for cases on the west coast of the US.

A tick becomes a host for Bb when it sucks blood from an infected animal or human. That tick can infect others when it attaches to another being and begins to feed on them. Ticks salivate excessively during feeding, and the bacteria are present in the saliva. Usually the tick needs to feed for over 24 hours before the Bb bacteria are transmitted to the host. The longer the tick feeds, the greater the chance that Bb bacteria will be transmitted to the host.

Once transmitted, the Bb bacteria will be attacked by the body’s immune system. This attack is what causes the symptoms that are present when an animal has Lyme Disease. Symptoms/clinical signs are different for humans versus dogs versus horses. For the purpose of this post, we will only focus on horses.

Now I’d like to focus on what makes Lyme Disease a Misused, Misunderstood, and Misdiagnosed disease.

#1 – Large Variety of Clinical Signs

Below is a graphic listing some of the clinical signs that have been seen in horses with Lyme Disease.

Important factors to consider:

- Not every horse infected with Lyme Disease will develop all of these signs.

- Several of these symptoms are difficult to recognize (low-grade fever, skin sensitivity).

“For some reason humans like to have one explanation for everything, so our minds will want to look for one disease that causes all of these problems. Lyme Disease is such an easy way to explain all of these issues and it is treatable! However, things are not usually that simple.”

#2 – Many other (and sometimes more common) diseases show similar clinical signs

Lets look at a few examples.

Case 1: A performance horse has had chronic weight loss, poor performance, and some behavior changes (lethargy) over the past 6 months. Based on the clinical signs listed above it seems like the horse is a shoe-in for Lyme Disease diagnosis. However, as we gain some more history on the horse we find that it is a nervous horse and many times will not eat his grain. Based on this information, the vet decides to perform endoscopy and look at the stomach for evidence of ulcers. In this case it is highly more likely that gastric ulcers are causing the horse to not eat, lose weight, and become more lethargic.

Case 2: An older horse is a pasture ornament for 90% of the time, but sometimes the owner really feels like taking him camping and riding for 3-4 days over rugged terrain. The horse always is sore and lame after the first day, but it is a different leg each time. He seems fine after getting home and spending some time resting though. Again – Lyme Disease fits right in with a reasonable diagnosis. But after using some common sense, we can assume that the owner needs to keep her horse in shape and not expect him to be a weekend warrior.

There are myriads of issues that can have the same symptoms as Lyme Disease, and sometimes more than one problem can be happening at once. For example, a mare might be in heat (which causes behavior changes and hypersensitivity) and have a injured tendon (causing lameness and swelling). For some reason humans like to have one explanation for everything, so our minds will want to look for one disease that causes all of these problems. Lyme Disease is such an easy way to explain all of these issues and it is treatable! However, things are not usually that simple.

# 3: Lyme Disease is not easy to definitively diagnose

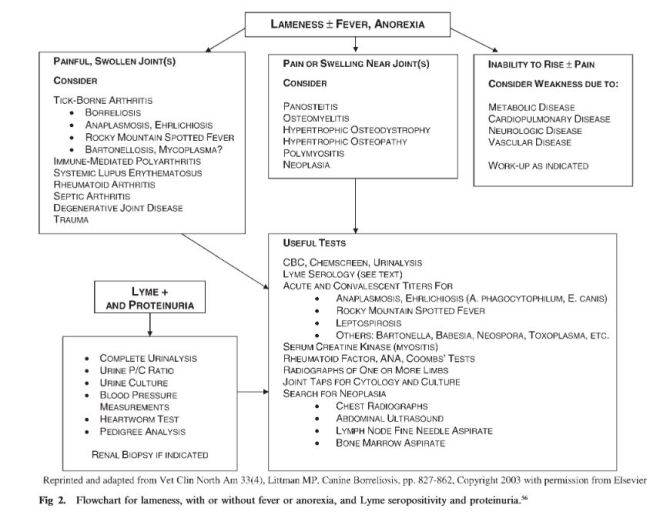

Like EPM, a diagnosis of Lyme Disease is not simply a test with a positive or negative result. To reach a diagnosis of Lyme Disease, the vet has to use deductive reasoning and their experience. For an example I would like to point to a graphic used by veterinarians when trying to make a diagnosis of Lyme Disease in a dog.

When a vet is presented with a horse that is a Lyme Disease suspect (is showing appropriate clinical signs) they must ask themselves several questions:

- Does the horse live or has it been to an area where ticks that carry Bb are present or endemic?

- Have ticks been found on the horse?

- Have other disorders that cause similar signs be ruled out?

If the answer(s) is(are) yes to those questions, then the next step is to draw a blood sample and send it in for testing. Usually the test is looking for the presence of antibodies to Bb present in the horse’s blood. The presence of the antibodies indicate that the horse has been EXPOSED to the Bb bacteria. It does not tell us if the horse currently is infected and fighting Lyme Disease. For that answer we have to look at the number and type of antibodies present in the blood.

Large numbers of antibodies in the blood typically indicate an active infection, but these numbers are all relative. There are no exact cutoff numbers that say “if your horse has X amount of antibodies then they should be treated for Lyme disease”. The decision on whether to treat or not is best left up to your veterinarian, who has clinical training and experience in determining what horses might benefit from treatment. For more information on testing and interpreting results, I refer you to this nice summary from Cornell University.

To summarize: Diseases that have many vague and intermittent symptoms are easy to jump to as a diagnosis for any ailment your horse may face. This is especially true when there is no diagnostic test that is clear cut, and when treatment may or may not improve the clinical signs of the disease. Too often these type of maladies are misused by horse enthusiasts to explain all of the problems that they see in their horse, mostly because the disease is misunderstood. It would be best for the horse if we can keep an open mind and scientifically search for a correct diagnosis, instead of conveniently jumping to diseases like EPM and Lyme Disease.